Colonist A

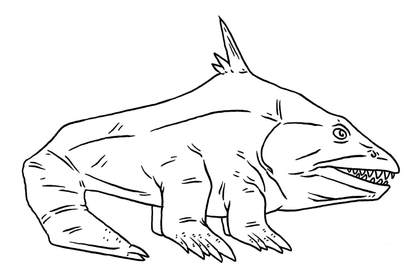

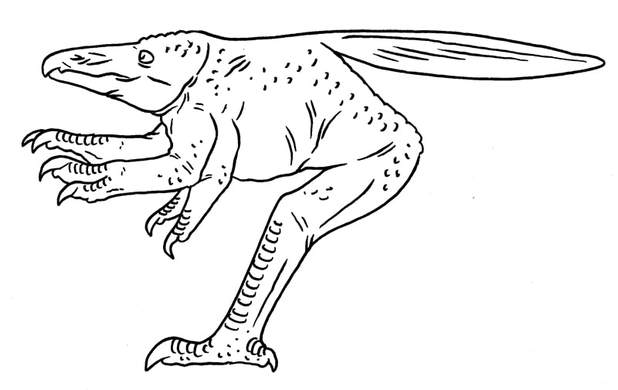

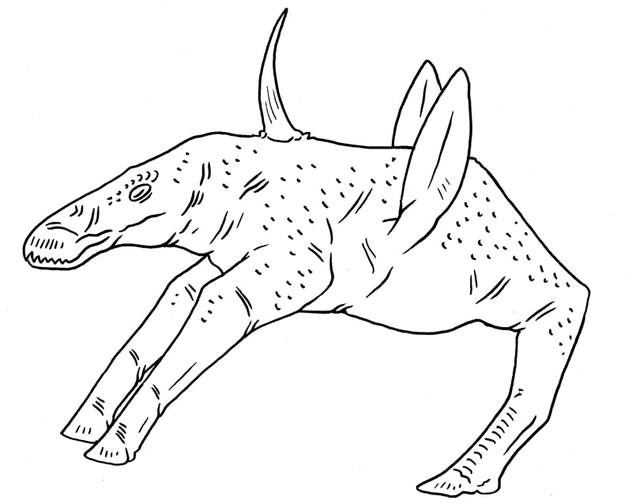

Firstly, we have this odd hopping creature, the Five-footed Hopper (Terrichthys saltator). With what appear to be five limbs and a spine upon its back, you would barely ever guess that this tropical land-dweller were a fish. Pectoral and pelvic fins form the 2 pairs of clawed forelimbs, and a modified tail forms the rear foot. Its gill chamber is expanded and acts much like a lung, as it breathes through a spiracle-like gill-opening. Remnants of the dorsal fin form a defensive spine to deter predators.

The original ancestor of this oddity, during the waning years of man was the Rock Goby (Gobius paganellus). Gobies and their relatives have expanded into amphibious roles during our time, mudskippers for example. So eventually, over 450 million years, a crawling and leaping goby became the ancestor you see in the previous picture.

As the ensuing 180 million years wore on, this species gave rise to the Fivefooter clade (Quintapoda), which eventually came to dominate the landscape as the main dynasty of large animals. The clumsy arrangement of 5 “limbs” became elongate, muscular, and jointed, just as efficient in form and function as any belonging to a tetrapod. Both herbivores and carnivores have evolved, some filling niches not unlike those once found on earth. Gill chambers have become a large, powerful set of pharyngeal lungs, and the back spine would variously be used for defence, balance or visual signalling. The Cloaca is usually between the middle pair of limbs, and faeces are squirted some distance to prevent fouling of the skin. Fertilisation is internal, using a penis-like organ; eggs have a leathery, waxy outer wall that protects them from desiccation, as most species lay them on land. Clutches of eggs vary in size depending on the species, but usually number less than 70. Five-footers will guard their nests, which are usually pits or scrapes in shady spots, though only a few kinds of five-footer actively care for their young.

Faunal Sample -

Five-footers come in all shapes and sizes, some rivalling Holocene megafauna in their majesty. The genus Quintabehemoth contains some of the largest five-footers, such as the Fismuth (Quintabehemoth sylvanus) of temperate continental latitudes. Reaching 3.7 meters tall and weighing as much as 6 tons, it is a huge and impressive creature. Its diet consists entirely of leaves and branches of tall trees and tree-like plants, which it gathers with the aid of clawed forelimbs. These animals have large pharyngeal teeth that form a heavy chewing mechanism; they often re-chew food much like a ruminant, fermenting the food in the large hindgut.

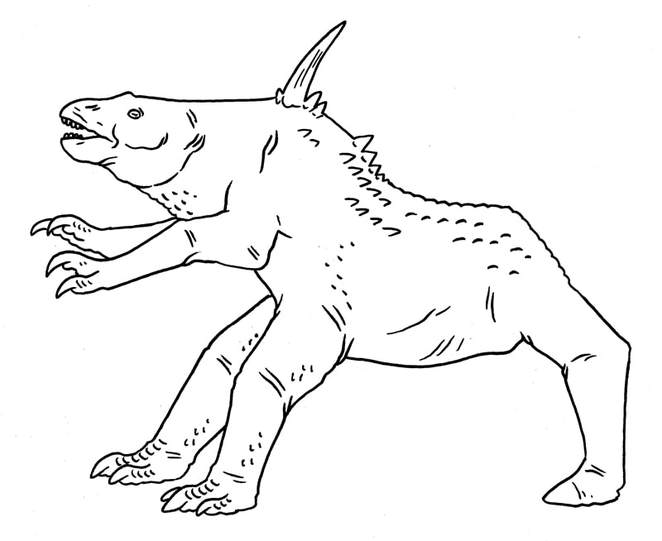

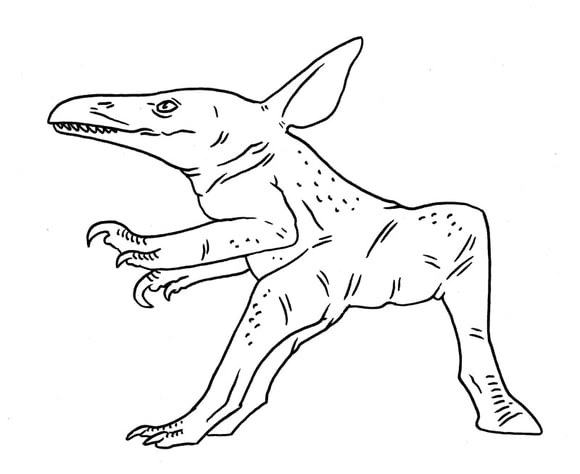

Formidable predatory five-footers can be found in most land-based ecosystems. The Greater Quintavenator (Quintavenator rapax) is a common large predator that extends from the temperate zone into the tropics in many places. Being about 100 kilograms in weight, it is similar in size and power to a lion, but kills its prey very differently. It will quickly overtake its prey in an ambush, making large blood-letting bites much like a predatory dinosaur.

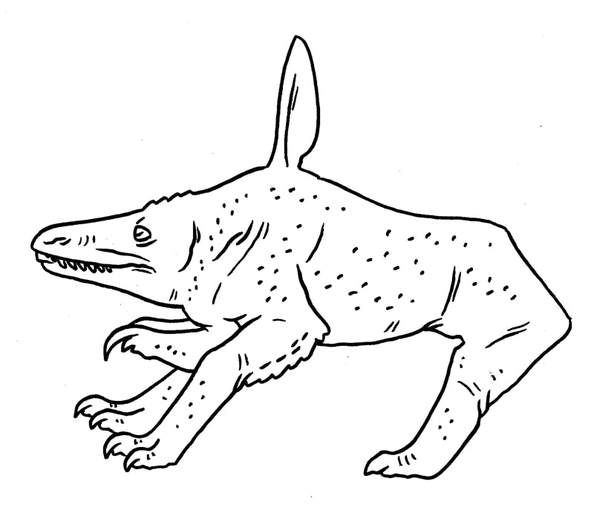

Not all five-footers retain five feet, just as not all tetrapods retained four. The Inchbeast (Mensurojaculus sp) is a smaller form that inhabits trees and shrubbery, moving in a measured inching motion when getting from place to place. It is a predator that ambushes prey by thrusting outward on its rear leg, and seizing the prey item with its clawed forelimbs. Inchbeasts are a moderate size, usually having a maximum weight of 5 kilograms.

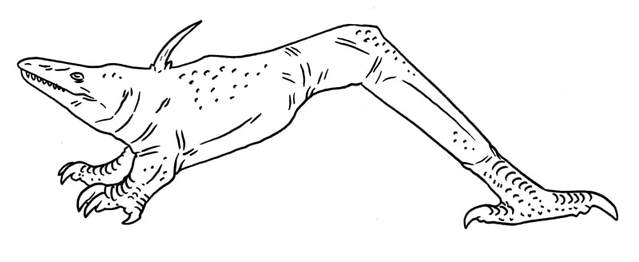

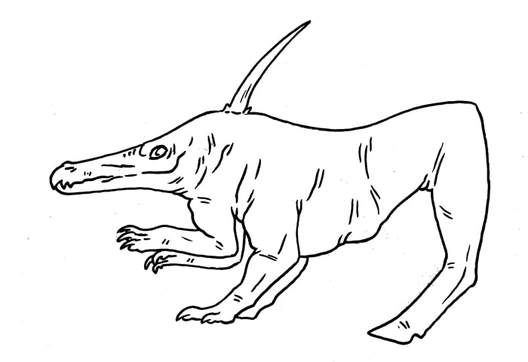

Adaptations for speed have led to extreme adaptations in this group, multiple times. Monopods (Genus Monomacropus) are mid-sized omnivores with a strong inclination towards meat, which are generally fast and agile. Bearing their weight only on a single foot, they are able to bound quickly after smaller animals, and are experts at evading larger predators. The fin-spine has become a long, flag-like balancing organ, and the forelimbs can be used for defence, or to seize and manipulate prey.

Bodies adapted for speed and agility must be different in the herbivores, as these must carry large hindquarters which house a fermenting gut. The Dun Tricerv (Tricervus medius) is a shy browser which is common in scrubby and forested areas, feeding at a middling level on understory plants. Unlike other herbivores, its chewing array is fairly simple, and its digestion less complete (as exhibited by its dung). Its fore-arms serve for pulling down branches but are also fine defensive weapons. Tricervs generally do not surpass 110 kilograms.

The undergrowth teems with various unusually-descended invertebrates, which are in turn fed upon by many vertebrate “insectivores”. Fhengis (genus Gobiosorex) are some of the most prevalent, generally as large as a rat. They meticulously rummage through the herbage or undergrowth, in search of arthropods, and will also dig a small ways into the ground to find worms and amoeba. At the slightest sign of a predator, they are able to bound away quickly on their hind foot. Often they are hard to swallow or grab because of their large defensive fin spine, which bears painful venom.

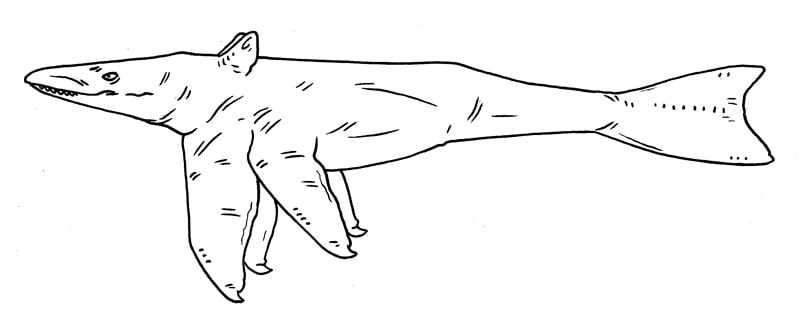

Ironically, these air-breathing fish descendants have in some forms, returned to the water. Seawhelps (Marephilopus jaculator) are 70-kilogram swimmers that ply tropical oceans in search of smaller fish-shaped amphibians. The rear foot has become a vertically sculling tail, and they must still breathe air as any traces of what was once their gills are not apparent. They are generally clumsy on land and usually never leave the water. Their “blow” upon reaching the surface is distinctive.

Flagbeeste (Antillogobius semaphore) are a member of a clade of exclusively herbivorous, grazing fivefoots. In most of these forms, the middle pair of legs is not used in locomotion, and variously serves as mating aids or display structures. They spend their days cropping low herbaceous growth of grass-like plants, and usually flee quickly at the first sight or scent of a predator. Their fin-spine is without venom, but can be brought to bear like a horn in defence, as it is made of solid bone. This species reaches a maximum of 190 kilograms.

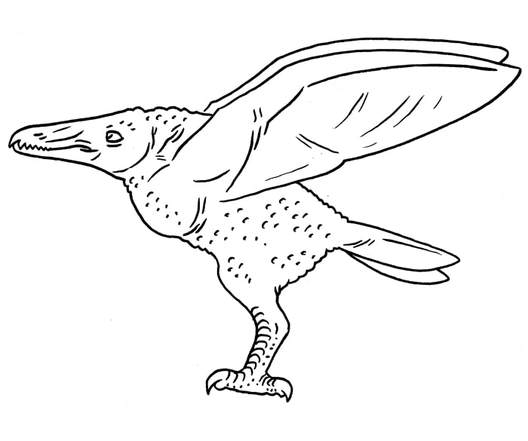

Amazingly, forms analogous to birds have arisen from the five-footers. These creatures usually only fly by day, and are far less varied than the birds once were. Fhrushes (Genus Gobiornis) are some of the most common, comprising some 25 species distributed across the globe, which vary greatly in colour. Being omnivores, they feed on invertebrates picked from shrubbery and undergrowth, as well as buds and seeds from various edible plants. They are fairly fast fliers, but do not compare favourably to birds.

In the equatorial jungles, tall trees bearing nutritious fruit are very common, and it is on this stage that has played out an unusual evolutionary saga. Black-backed Lunkeys (Piscatopithecus rex) are 60 kilogram tree-dwellers that feed mainly on fruit, but will gladly consume small animals and carrion. Unlike most five-footers they exhibit a keen intelligence, comparable to parrots, and have complex social hierarchies. Young are born as a single leathery-walled egg which hatches into a well-developed baby, which receives parental care.